When conducting digital investigations, authorities often run up against the problem that the data they are looking for is stored on servers abroad or that service providers do not respond to requests. The European Commission is therefore working to develop uniform standards. A number of companies are already cooperating in these efforts.

The European Union intends to make it easier for the police and secret services to access servers belonging to Internet providers. This is set out by a position paper by the European Commission on gaining access to e-evidence, which was discussed at the recent Justice and Home Affairs Council. The paper contains proposals for implementing the Council conclusions on “Improving criminal justice in cyberspace” of June of this year. Allowing authorities to submit direct enquiries to companies is on the table.

International judicial assistance or direct enquiries?

This is predominantly an issue concerning operators of cloud services in the USA. While a mutual judicial assistance agreement in criminal matters is already in place between the European Union and the USA, European investigators consider the legal steps that this entails to be too cumbersome and time-consuming. This emerged from the responses to a questionnaire that was answered by authorities from 24 member states. It transpired that investigators often take different approaches to gaining access to e-evidence.

A number of authorities prefer to submit their enquiries directly to providers. Only seven governments believe that providers are under obligation to produce data while 14 governments consider their responses to be voluntary. There is often confusion also among companies as to the circumstances under which data must be produced. In certain cases, they believe it to be sufficient if the authorities are able to demonstrate that the relevant IP address is located in the investigating country. Other providers, on the other hand, always respond just as long as the address does not terminate in the USA.

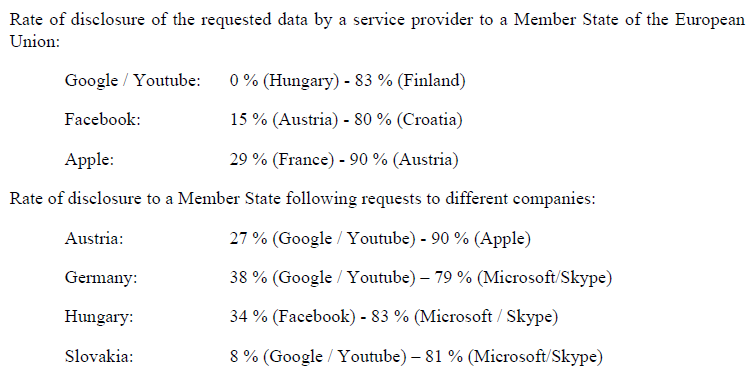

While companies also take different approaches to processing direct enquiries, this would appear to depend on which country is submitting the enquiry or what information is specified by the accompanying form on data types. Sometimes it is only personal data of account holders that is requested, and in other cases also traffic or content data. In a number of member states, applications can be made by police authorities, while in others these must come from the public prosecutor’s office or bear the signature of a court.

Council of Europe’s Convention on Cybercrime to be enhanced

In order to avoid these ambiguities, some member states have taken to requesting data within the framework of bilateral agreements, the EU agreement on mutual assistance in criminal matters or the Council of Europe’s Convention on Cybercrime. If the services are located in the European Union, then the new European Investigation Order (EIO) may also be deployed in the future, although the corresponding directive must first be transposed into national law by the member states.

However, legal clarity has yet to be established regarding whether the directive only applies to providers based in the European Union or who merely operate their servers there. The Commission is therefore to ascertain whether the scope of application of the European Investigation Order can be expanded to include providers that, while based in a third country, offer their services in the European Union.

At the same time, the Council of Europe is discussing the interpretation of the Convention on Cybercrime. It is also unclear here which data Article 18 (paragraph 1 (b)) governs. The wording of the legal text stipulates that the parties must empower their competent authorities to order “a service provider offering its services in the territory of the Party to submit subscriber information relating to such services in that service provider’s possession or control”. The members of the Council of Europe must communicate their positions with regard to this matter, which will then be discussed in the Cybercrime Convention Committee.

A number of authorities use “remote access”

Moreover, the Commission considers the varying competences of authorities in different countries to be in need of regulation. According to the questionnaire, some investigators are authorised to conduct investigations in the cloud even if the physical location of the servers is unknown. It also transpired that other authorities are even authorised to access servers remotely. The paper does not go into any detail about the respective technologies, but presumably these are Trojan programmes. Investigations of this nature are not permitted in eight of the responding countries.

The Commission’s proposals include setting up dedicated points of contact at the authorities of the member states and with Internet service providers. In Germany, judicial assistance between the Federal Police Force and foreign authorities is coordinated by the Bundeskriminalamt (Federal Criminal Police Office). Moreover, an Internet portal is to be set up where investigative authorities and public prosecutors can liaise and store their points of contact as a first step. The platform could be expanded at a later stage to enable requests to reach multiple Internet providers with a single search query and to ensure that the authorities are able to provide each other with information regarding investigation orders that have already been submitted. As things currently stand, the portal will be established under the auspices of the Council of Europe.

Talks with Internet giants

The second EU Internet Forum was held on the fringes of the meeting of the Justice and Home Affairs Council in Brussels last week, to which the Commission and Europol had invited several US Internet providers, including Twitter, Facebook and Google. E-evidence was also a topic of discussion at this meeting.

Moreover, this issue was also on the agenda of the latest U.S.-EU Ministerial Meetingon Monday last week. The government in Washington was represented by the U.S. Attorney General and the Secretary of Homeland Security. These discussions are now set to be continued by the “practitioners”, which, in the case of the European Union, include investigative authorities and public prosecutor’s offices, i.e. Europol and the EU’s Judicial Cooperation Unit Eurojust.

Microsoft, Google, Apple, Twitter and Facebook attended a first workshop. The European Judicial Cybercrime Network (EJCN), which the public prosecutor’s office in Frankfurt am Main is participating in as the central department for the fight against Internet crime, is to be charged with continuing this work. The EJCN has announced an initial work programme for the coming weeks. The Commission has set aside a first tranche of funds to the amount of one million euros to support this work; the money will presumably be spent on a study concerning the legal scope for judicial assistance and/or direct enquiries. The results are to be presented in June next year.

Image: All rights reserved Julian King/ Twitter.