The EU is taking its maritime surveillance to a new level. The three agencies responsible for coastal and maritime surveillance are to be merged. 81 million euros has been earmarked for unmanned aerial vehicles alone, with hundreds of millions also being spent on the necessary satellite capabilities. The money is flowing into the coffers of arms companies.

The FRONTEX border agency, the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA) and the European Fisheries Control Agency (EFCA) have signed a new cooperation agreement. Its aims include improving border surveillance, intercepting vessels suspected of “engaging in criminal activities” and combating illegal fishing. The agreement was signed on the margins of a conference at which the agencies discussed new forms of maritime surveillance, information sharing and capacity building.The agreement was signed by the executive directors of the three agencies at the Frontex headquarters in Warsaw. Symbolically, it is a sign of things to come for the EMSA, EFCA and FRONTEX, as the agencies responsible for coastal and maritime surveillance are to be merged by the end of this year. To this end, the European Union has established a pilot project involving the three agencies in the framework of the Contact Group on European Coast Guard Functions. The European Border and Coast Guard (EBCG) had been under discussion as the name of the future agency, but it will probably continue to be called FRONTEX.

Tracking vessels: EUROSUR

The three agencies are already working together to combat “illegal activities” such as arms, cigarette and drug smuggling. The new agreement is primarily intended to enhance their technical surveillance capabilities, however. The EMSA, EFCA and FRONTEX use satellite reconnaissance services in their work and share reconnaissance data. The European Maritime Safety Agency assists FRONTEX in tracking ships, with further reconnaissance data coming from the European Union Satellite Centre (SatCen).

FRONTEX runs the EUROSUR surveillance network, which is also satellite-based. Relatively large vessels off the coast of Libya and Turkey are already being monitored for suspicious behaviour. For example, movements of cargo ships which have reached the end of their operating lives but not yet been scrapped could be an indicator that they are being used in “migrant smuggling”. FRONTEX can automatically track several vessels simultaneously. The space-based surveillance uses pattern recognition. The Federal Ministry of the Interior provided the following information recently in its answer to a minor interpellation:

“The basis of the selective monitoring concept is the combination of existing data from service providers (e.g. the IMO (International Maritime Organisation) or MMSI (Maritime Mobile Service Identity)) with special anomaly algorithms and forecasting tools, which can provide information about vessels’ past, present and potential future movements. Based on intelligence notifications from the Member States or predetermined anomaly parameters in certain sea areas (e.g. the operational areas of the Frontex operations Poseidon Sea and Triton), a number of unusual vessel movements indicating the possibility of illegal migration can be identified from among the countless vessel movements in the Mediterranean.”

FRONTEX is the first user of the Airbus SpaceDataHighway

The automated satellite reconnaissance capabilities were developed in the framework of the European Union’s Copernicus programme. The aim was to provide services for environmental monitoring and for security concerns. The programme’s original name was “Global Monitoring for Environment and Security” (GMES). For many years, however, reports focused solely on the environmental aspects of GMES; only gradually have its security applications become more widely known. Copernicus is, for example, the first user of the brand new “SpaceDataHighway” produced by Airbus. For half a billion euros, the arms company is installing a satellite relay system which will hugely speed up data transmissions. FRONTEX is now using the SpaceDataHighway to operate drones.

The director of the EMSA recently announced that large, high altitude drones are to be deployed in the Mediterranean before the end of this year. The European Commission regards the drones as a tried and tested “tool in the overall surveillance chain”, and describes the use of unmanned aerial vehicles as a cheaper alternative than manned patrol aircraft. These services are to be leased, and a call for tender has already been published. To “increase the surveillance capability” of FRONTEX, the EMSA is receiving an additional 81 million euros in funding for the period to 2020. Most of this money is being spent on the procurement and operation of the drones, with around a quarter going to finance the needed satellite capabilities.

In the summer, the joint capabilities of the EMSA, EFCA and FRONTEX are to be tested in practice for the first time. They are to cooperate in the framework of Operation Triton, the FRONTEX operation to monitor the Italian Mediterranean coast to combat “migrant smuggling”.

Fully autonomous flight trials of drones announced

Since 2013, the EU has been funding the RPAS-ATM Integration Demonstration (RAID) project to trial the operation of unmanned drones in civil airspace. The project is part of the Single European Sky ATM Research (SESAR) programme to create a single European airspace. SESAR aims to standardise the national air traffic management systems and procedures in the European Union, leading to a single “air traffic management network” by 2020. This also affects large drones.

The RAID project, led by the Italian Aerospace Research Centre, is intended to contribute to the implementation of the European Commission’s roadmap for integrating civil drones into the general aviation system (video). By 2018, visual line of sight operations are to be permitted, with operations beyond that permitted by 2023. From 2024, drones will begin to operate in civilian airspace on an equal basis. Four years later, drones will probably be allowed to take off from and land at civil airports. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) is working to a similar timeline.

RAID initially carried out extensive simulations using an “optionally piloted vehicle” (OPV), which can be converted to fly with or without pilots. The results of the simulations were presented at a conference held by the Italian military, which itself operates various types of large drones and which is also interested in RAID. A series of flight trials are now to follow, with the OPV operating fully autonomously in some cases.

Earlier trials using Heron drones

The trials will also cover cooperation with air traffic controllers, who are to treat the drones like normal aircraft. To this end, unmanned aerial vehicles can be equipped with a text-to-speech system which provides the air traffic controllers with the status reports they normally receive by radio. The trials will also look at emergency situations, such as loss of communication while an automatic collision avoidance system is in use. The results of the flight trials will be published at the end of the RAID project in June.

The European Union is running a similar project entitled “Demonstration of Satellites enabling the Insertion of RPAS in Europe” (DeSIRE II), which is examining the use of satellite navigation for the control of large drones. It aims to develop procedures to ensure flights are safe even in the event of communication being lost. DeSIRE is being funded by the European Defence Agency and the European Space Agency. The lead organisations involved are Italian institutes and military bodies and the European Fisheries Control Agency.

The German Aerospace Centre (DLR) was involved in simulations during an earlier stage of the project, and worked together with the Spanish coast guard. A Heron 1 drone was used, the same type deployed by the Bundeswehr in Afghanistan. The first flight trial took place in Murcia, Spain, with the drone flying above 6000 metres. A Spanish military aircraft approached the drone head-on and from the side to simulate an impending collision. The pilots of both aircraft then followed the instructions of the air traffic controllers in Barcelona.

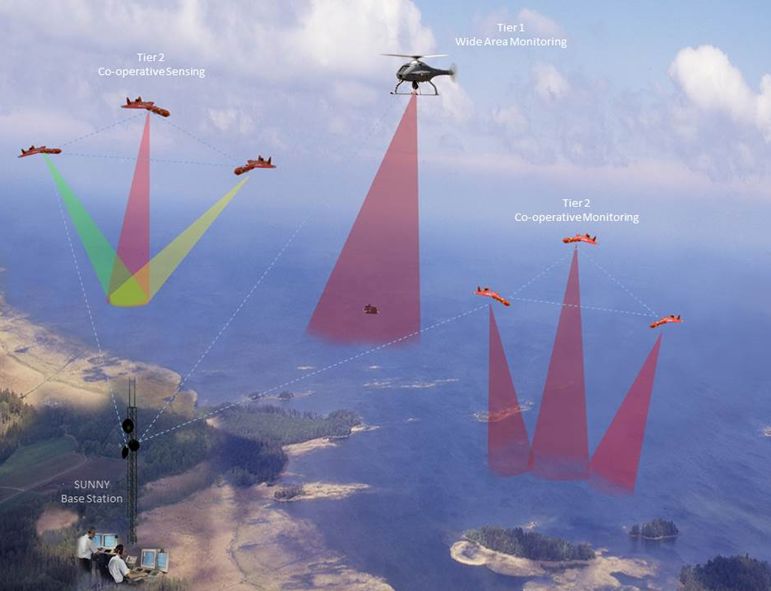

Image: All rights reserved EU research project SUNNY.