The EU Border Agency has massively strengthened its surveillance capabilities. To make better use of this information, it will now be passed to the Libyan Coast Guard. This is legally impossible, now Frontex is pressing for the relevant regulations to be renewed. The navy in Libya, however, is using a Gmail address.

Libya is to be connected to the European surveillance network “Seahorse Mediterranean” before the end of December this year. This was written by the State Secretary at the German Federal Foreign Office in response to a parliamentary question. Libyan authorities could learn about relevant incidents in the Mediterranean via the new cooperation. The military coastguard, for example, would receive the coordinates of boats with refugees to bring them back to Libya.

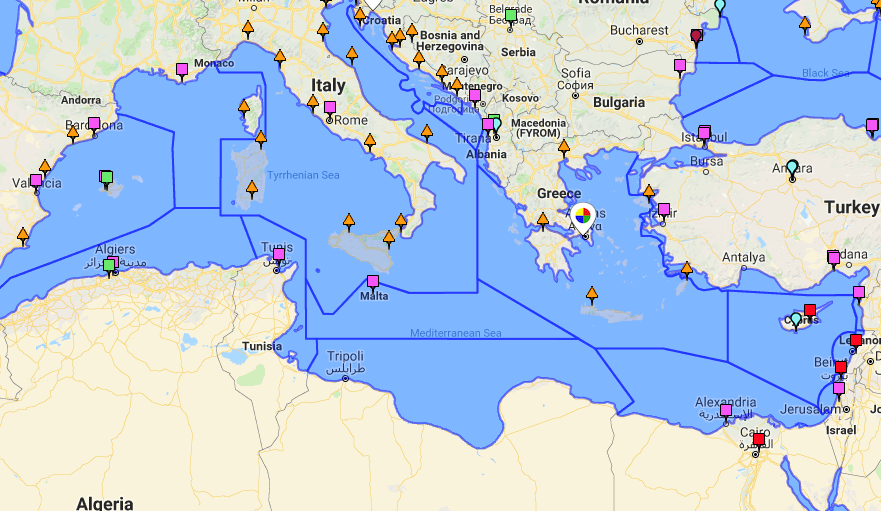

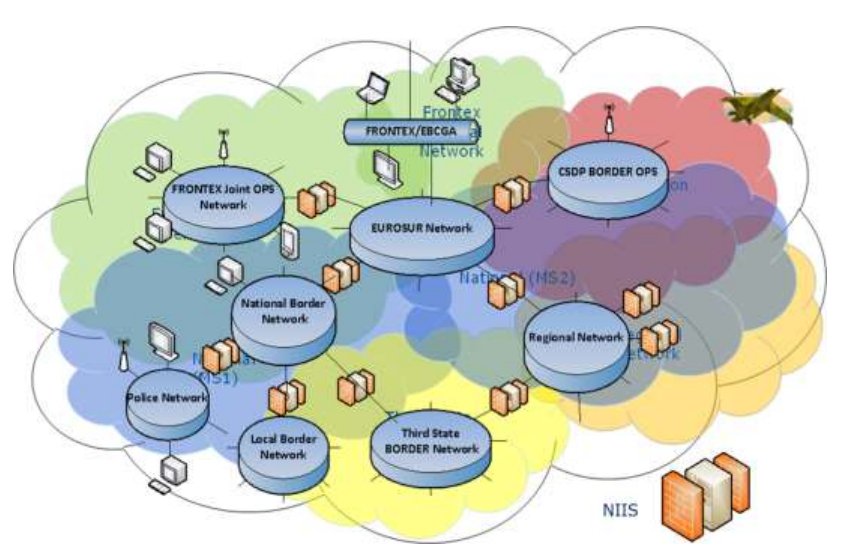

In “Seahorse Mediterranean” the southern Mediterranean countries of the European Union are joined. In addition to Italy, Malta, Greece, Cyprus, France and Spain, Portugal is also part of the network. It is a multilateral network of some Member States, not an institution of the European Union. “Seahorse Mediterranean”, however, it is connected to the EUROSUR system through which the European Union monitors its external borders. EUROSUR is intended to contribute to an “integrated European border management”.

Monitoring with satellites and long-range drones

The EUROSUR system is operated by the new European Border and Coast Guard (EBCG) and coordinated through a Situation Centre at the Frontex Border Agency in Warsaw. In this way, information from Frontex can also be fed into “Seahorses Mediterranean”. These can be, for example, situation reports or event messages generated from satellite reconnaissance information from the Copernicus programme. Frontex uses surveillance from space to detect suspicious activities at external maritime borders.

Following the launch of the EUROSUR programme and the new Frontex Regulation in 2014, further aerial surveillance capabilities were added. In October 2017, Frontex launched the Multi-purpose Aerial Surveillance (MAS) programme. According to the latest annual report on EUROSUR, the system has already assisted in the detection of several refugee boats. Two months ago, Frontex also launched a programme to monitor the Mediterranean with long-range drones.

Frontex calls for green light

With Libya’s connection to the “Seahorse Mediterranean”, its authorities can also benefit from the modern capabilities. Frontex is responsible for monitoring the entire Mediterranean Sea, including Libyan territorial waters. These are part of the European Union’s so-called “pre-frontier” area, which Frontex is required to monitor under the EUROSUR Regulation. The area of interest has recently been extended to 500 square kilometres off the North African coasts.

Before exchanging information in “Seahorse Mediterranean”, the participating EU states conclude an agreement with Libya. In the case of sensitive information or personal data, Frontex would also have to negotiate a so-called status agreement with the government in Tripoli.

At present, however, there is no European Union regulation allowing Frontex to cooperate more closely with Libya. This assessment is substantiated in an assessment by the scientific services of the German Bundestag. In its annual report on the External Maritime Borders Regulation, Frontex therefore called for the green light for cooperation with the Libyan coastguard.

The flow of information is to be regulated

For example, the current External Maritime Borders Regulation prohibits the exchange of personal data of intercepted or rescued persons with third countries where “there is a serious risk of contravention of the principle of non-refoulement.”. According to the text, this applies to countries where “there is a serious risk that he or she would be subjected to the death penalty, torture, persecution or other inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment”.

EU law is also binding where Member States participating in Frontex missions have concluded their own data-sharing agreements with a third country, as in “Seahorse Mediterranean”. Any transfer of information by Frontex or Italy to Libya could therefore be seen as facilitating non-refoulement.

In the future, however, the controversial flow of information should be regulated by law. Council and Parliament are negotiating the new version of the EUROSUR Regulation, which then has to be adopted by Parliament. EUROSUR is to receive an additional 52.5 million euros in 2020, and a yearly additional 90 million euros from 2021 till 2027. Most of the money is earmarked for the application of new technologies, but EUROSUR is also to receive 65 new employees. Additional funds are to be granted through the research framework programme “Horizon 2020”, with the help of which EUROSUR is to develop new information services and surveillance technologies.

Far beyond previous cooperation

According to the Commission’s proposal for the new EUROSUR Regulation, the southern Mediterranean countries should cooperate with the Libyan coastguard whenever there is a “medium”, “high” or “critical” risk at border sections. The competent National Coordination Centre will then liaise with the competent authority of the neighbouring third state.

As of Article 72, the proposed regulation contains a separate section with provisions on the transfer of data to third countries. At the moment, the Member States are agreeing on a common position in the Council. Some governments are calling for the Commission to provide more financial support to those Member States which have concluded bilateral or multilateral agreements with third countries. The exchange of data should also be permitted if it contains “confidential security information”. The wording thus goes far beyond previous cooperation.

“Military operations with a law enforcement purpose”

The current Regulation on the European Border and Coast Guard is also currently under discussion. A Commission proposal has caused a sensation because Frontex wants to set up a standing border troop of up to 10,000 officials and carry out missions in third countries. However, the Commission also sets out the legal basis for Frontex’s data exchange with third countries “either in the framework of bilateral and multilateral agreements between the Member States and third countries including regional networks or through working arrangement established between the Agency and the relevant authorities of third countries”.

This wording is tailor-made for the regional “Seahorse Mediterranean” network. Member States are even directly invited in the paper to extend cooperation with third countries “at operational level”. Explicit mention is made of “military operations with a law enforcement purpose”.

It is yet unclear with which concrete bodies Frontex and the EU Member States should network in Libya. This year the Libyan government has declared a sea rescue region for which its coastguard on the high seas is to be responsible. This zone borders the rescue area of Malta, Italy and Tunisia. But Libya does not have a Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) to manage this SAR region.

“Multipurpose equipment for maritime surveillance”

Libya is now being supported by Italy to set up such a MRCC. The European Union is financing the project with 42 million euros from the Emergency Aid Trust Fund for Africa. An additional two million euros come from the EU’s internal security fund, another two million from Italy. The MRCC will later have modern facilities for monitoring the territorial waters, the 24-mile zone and the extensive SAR region.

Further funds could follow the decision of the new EUROSUR Regulation, which obliges Frontex to provide technical and operational assistance for similar measures. A renewed Integrated Border Management Fund will also provide funds to Member States for “multipurpose equipment for maritime surveillance”. According to a decision of the EU Parliament, 35 percent of the more than one billion euros per year would be spent on surveillance of the external maritime borders from 2021 onwards.

Libya copies EU model

However, the MRCC is not supposed to be operational until 2020, so the centre is out of the question for a connection to “Seahorse Mediterranean”. In the meantime, however, the Libyan government has set up a further situation centre in which all the authorities responsible for maritime security have joined forces. This Libyan “Rescue Coordination Centre” (JRCC) is located near the airport in Tripoli. According to the German government, employees of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Coast Guard, the port and airport authorities as well as the Telecommunications Office are represented there.

Libya is thus copying the idea of so-called “national coordination centres” as set up by the EU Member States for the decentralised EUROSUR. According to the EU Commission, this inter-agency cooperation is to be transferred to third countries in order to establish “regional cooperation networks”. In this respect, the networking with “Seahorse Mediterranean” is also likely to take place via the JRCC. In fact, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) reports that the JRCC is temporarily assuming the function of an MRCC in its Register of Maritime Rescue Centres, which can only be accessed after registration. On the other hand, the public “Search and Rescue Contacts” website operated by Canada does not mention that the specified MRCC is only a temporary facility.

Navy and Coast Guard use Gmail address

It is also puzzling, however, that the Libyan coastguard has given a Google e-mail address as a contact for the makeshift MRCC. While the JRCC has an address for the government’s domain in Libya, the MRCC is to be contacted via lcg.nav.room@gmail.com. Sea rescue organisations complain that Libya’s coastguard does not respond to telephone calls, so that communication must actually take place via e-mail addresses. In a US government document collecting monthly sea rescue cases, even the Libyan Navy can be found with a Gmail address.

One reason could be that the Navy and Coast Guard in Libya consist of militias who are loyal to the government in Tripoli, but who are actually independent. These troops repeatedly hit the headlines for their brutality towards refugees and sea rescue organisations. The Libyan government now wants to shrink the powers of the militias. At first, government troops brought the airport under their control, and later the port guards are to be removed from the militias.