The shifting of the EU’s external borders to North Africa is generating profits for defence companies

The European Union is stepping up efforts to protect its external borders. The focus is on developing the Frontex Border Agency into a European Border and Coast Guard Agency. Another pillar of EU migration policy is the transfer of border security to third countries. Particular attention is paid to the maritime borders in Libya and neighbouring countries. Furthermore, most of the migrants reaching the European Union via the Mediterranean come from Libya. Their absolute number is declining, yet in 2017 almost 119,000 people fled.

The fragile “unity government” in Tripoli controls only a fraction of the land borders. However, their military coastguard and civilian maritime police are responsible for those stretches of the coast from which many depart for the EU. Shortly after the fall of Muammar al-Gaddafi in 2011, the EU wanted to integrate the Libyan coastguard into its surveillance systems. Control centres in Tripoli and Benghazi should be connected to a Mediterranean Cooperation Centre (MEBOCC) based in Rome. Border authorities from Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, Malta, Greece and Cyprus are joining forces there and communicating via the “Seahorse Mediterranean” network.

The civil war between various rebel groups thwarted the planned cooperation. In a new attempt, a control centre in Tripoli is now to become part of “Seahorse Mediterranean”. As the first non-European member, the notorious Libyan coastguard would then have access to information from the EU surveillance system EUROSUR. The reconnaissance data distributed there comes from EU military missions, Frontex, but also from the US command Africom in Stuttgart or the EU Satellite Centre. Cooperation should not be limited to Libya. The European Commission is planning to connect Tunisia, Algeria and Egypt under the project name “Seahorse 2.0”.

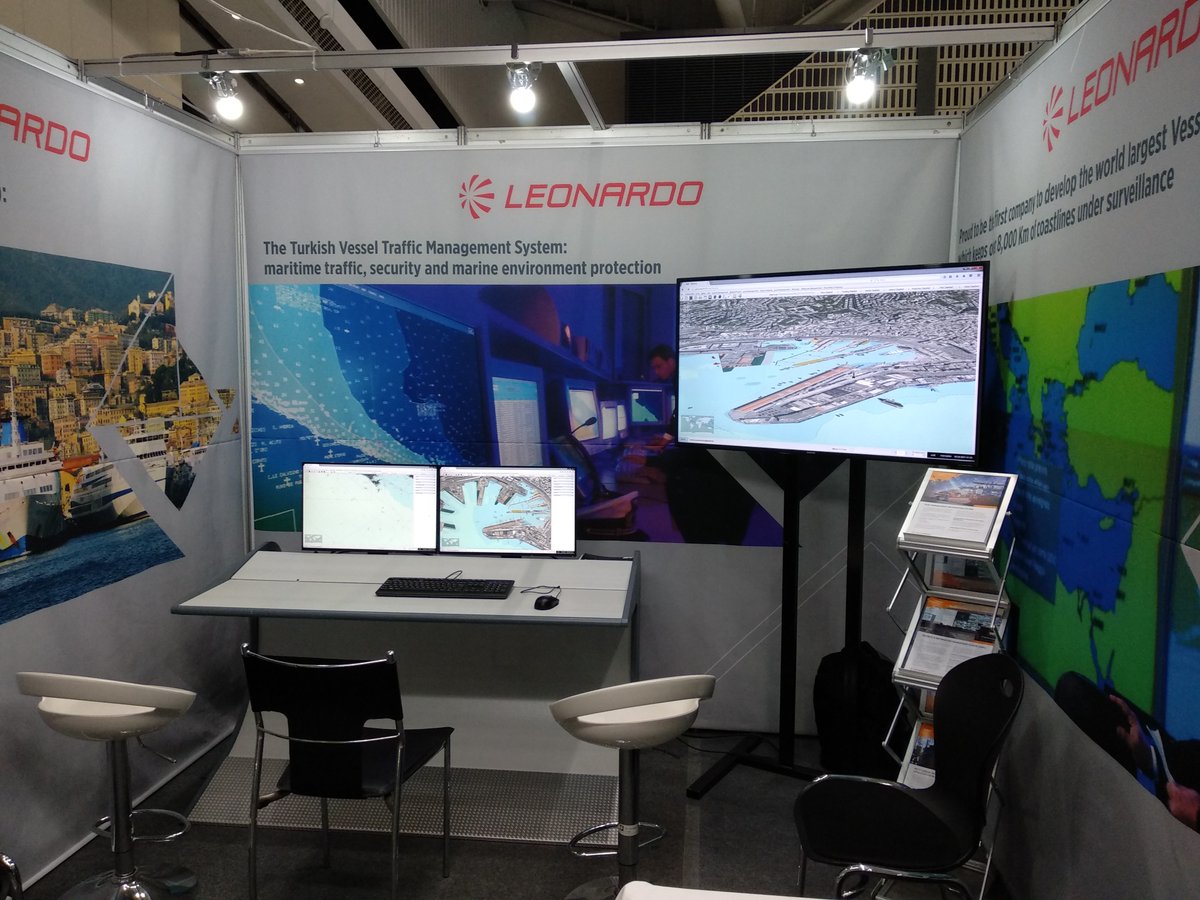

Italian and Libyan security authorities have already opened a bilateral control centre in Rome. However, Libya must set up its own facilities to participate in European networks. There is already a maritime control centre in the centre of Tripoli, in which the coastguard, navy, border police, coastal police and port authorities are involved. The installation does not have an electronic Vessel Traffic Management System (VTMS), all radar equipment was destroyed during the revolution.

The Italian Coast Guard and the Spanish Guardia Civil are now helping to equip and train the new technology, which includes radar equipment and drones. By 2023, the Libyan authorities are to receive 285 million euros for the expansion of border surveillance from Rome and Brussels. The EU Commission alone is funding the establishment of several “operational control centres” with 42.2 million euros.

Italian authorities are also helping Libya to apply for a sea rescue zone off Libyan territorial waters. One of the conditions for such a SAR zone is that the International Maritime Organisation will set up a sea rescue centre, which will also be set up by Italy. The European Commission supported the project with a feasibility study. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) leaves rescue equipment and tablet computers to the Libyan Coast Guard to manage returned migrants.

It is still unclear who will be awarded with the contract for the control centres in Libya. The German-French Airbus Group, Leonardo (Italy), Thales (France), Indra (Spain) and Signalis, now also part of Airbus as the Maritime Surveillance Centre, are all developing and marketing such systems. They can be extended and can integrate technology for coastal surveillance, ship observation or coordination of rescue measures.

Depending on the equipment, the maritime surveillance systems incorporate images from satellite reconnaissance. To ensure that information reaches ground stations even faster, Airbus has installed the “space data highway” consisting of laser-based communication satellites for one billion euros. Frontex was the first customer.

Navigation data from the Automatic Identification System (AIS) and the Long Range Identification and Tracking System (LRIT) are also used to identify larger ships. Software automatically assesses whether a ship could be suspicious because it is taking an unusual course or is moving at a conspicuous speed. In addition, radar systems, cameras and infrared sensors are installed either permanently on the coast or from ships and aircraft to improve the situation.

The sale of border surveillance technology is a growth market which should secure high profits over years. Airbus for instance sells ground surveillance radars, high-resolution binoculars and night vision equipment. Two years ago, the company advertised the technology on its website as particularly suitable against a “wave of illegal immigrants” which would hit Europe’s southern coasts and islands.

Now the EU wants to further improve sea-based monitoring systems. The Ministries of the Interior and Defence from Italy, Portugal, Greece and Spain are conducting research together with European defence companies in the “Maritime Integrated Surveillance Awareness” (MARISA) project. The platform to be developed should bring together as many data sources as possible. In addition to geographical and satellite-based information, social networks on the Internet are also being searched. With the help of algorithms, disturbances should be detected or even predicted as early as possible. Again lucrative orders await for the defence and surveillance industry.

Image: VTMS from Italian Leonardo (all rights reserved Leonardo).